www.DarbyRangers.Com | Follow Me

" History is Philosophy teaching by example and also by warning;

its two eyes are geography and chronology..."- Anon

No. 11 (Chapter 4)

|

Selected Combat Operations

in

World War II

|

Leavenworth Papers (1)

Unclassified

by Dr. Michael J. King

Combat Studies Institute

US Army Command and General Staff College

Fort Leavenworth, Kansas

June 1985

Cisterna:

The Rangers' experience in Italy fell into two phases. The first phase began with an amphibious landing at Maiori, near Salerno, on 9 September 1943, and included the subsequent seizure and defense of Chiunzi Pass, the drive on Naples, and prolonged fighting on the Winter Line. The second phase began with the amphibious landing at Anzio on 22 January 1944 and came to an abrupt end eight days later with a disastrous operation at Cisterna di Littoria, or Cisterna. In the latter action, all but 6 men of a 767-man Ranger force were killed or captured by the Germans.

The Rangers' defeat at Cisterna was due to several causes, but one of the factors that contributed to the battle's outcome preceded it by several months and is worth examining in detail at this point. This was the decline in the unit's combat skills resulting from the dilution of a well-trained, extremely cohesive unit by less well-trained replacements for those original members who had become casualties. Ironically, the Rangers suffered most of these casualties when the force was used as conventional infantry rather than as the special strike force that it was. These casualties began to mount immediately after Salerno.

Darby's Ranger Force was attached to the British X Corps for Avalanche, Fifth Army's landing near Salerno. The Rangers came ashore at Maiori, about twenty miles west of Salerno, before daylight on 9 September with the mission of taking the town, destroying nearby coastal defenses, seizing Chiunzi Pass, and preparing to operate against the rear of Germans who might attempt to hold up the Allied advance through neighboring Vietri Pass. The Rangers gained local surprise and had accomplished their objectives by midmorning.

Had the other Allied units been as successful, they would have quickly driven inland and on to the Plain of Naples. Unlike the Rangers, however, the main invasion force did not have the advantage of surprise when landing, and nightfall saw it fail to achieve most of its D-day objectives. Furthermore, once the beachhead was established, Fifth Army was slow to break out of it, and the Rangers' mission that had been expected to last no more than two days thus lasted more than two weeks. During that time, the Rangers were subjected to successive German counterattacks and pro-longed artillery fire. The X Corps, which controlled the invasion force landing west of Salerno, did not begin its drive to the Plain of Naples until 23 September and did not succeed in reaching it until five days later.

The 1st and 3d Ranger Battalions won Distinguished Unit Citations for their successes at Maiori and Chiunzi Pass but paid a very high price. In the two weeks preceding the drive on Naples, Ranger Force lost 28 killed, 9 missing, and about 66 wounded.' All but a few of these casualties, which numbered about 20 percent of the Rangers' authorized strength, were suffered during the conventional fighting that followed the seizure of Chiunzi Pass-- the type of fighting the Rangers had neither been created nor organized to do.

(3)

(3)A relatively uneventful drive on Naples followed and led to about a month and a half of conventional infantry combat on the Winter Line. The heavy losses that the Rangers had sustained at Chiunzi Pass were repeated in the new fighting, and during the week which ended on 27 November, Ranger Force suffered more than seventy killed and wounded."

The regular use of the Rangers for conventional missions disturbed many of Darby's men. On 28 November, Major Roy A. Murray, commanding officer of the 4th Ranger Battalion, wrote to the chief, Army Ground Forces, in an effort to resolve certain related problems. Murray pointed out that the Rangers did not have a clear-cut directive that defined their purpose and were thus hampered in long-range planning. Although a directive establishing that the 1st Ranger Battalion was to be for training and demonstration purposes had been issued on 1 June 1942, it had been superseded by events, and no consistent written or unwritten policy had ever replaced it.

Murray saw three problems as plaguing the Rangers. The first and most pressing was the replacement of casualties. After losing well-trained men in combat, the battalions had to remain out of action for a month or more to receive replacements and train them to Ranger standards. Murray recommended that the problem be solved by having trained replacements sent to Ranger Force from the 2d and 5th Ranger Battalions that had recently been activated at Camp Forrest, Tennessee.

The second problem, which was closely linked to the first, concerned the advancement of junior Ranger officers and the retention and use of experienced Ranger officers rendered unfit for combat by wounds or other physical disabilities. Murray recommended that some of the junior Ranger officers be given command of new Ranger battalions and that the disabled Ranger officers be sent to the United States to train Ranger replacements. His plan would allow younger men to advance and would still make use of the older men's experience.

The third problem was the absence of a Ranger Force headquarters to handle the administration, intelligence, planning, assignment of missions to the battalions, and, "most important," to decide if the missions were "proper" for the Rangers. Murray recommended that a headquarters be formed and given to Darby, "the senior Battalion Commander of Rangers. The fact that Murray described Darby as being only the Rangers' senior battalion commander reflected the tenuousness of Darby's control over the battalions he had organized. No documents are present in the Rangers' files to indicate that Army Ground Forces responded to Murray's letter.

On 17 January, Ranger Force made a practice amphibious landing at Pozzuoli Bay to the immediate west of Naples. The landing was part of a 3d Infantry Division exercise and a rehearsal for Anzio. Although the operation was a good opportunity for the Rangers and the Navy to practice working together, it revealed a serious deterioration of the Rangers' fighting skills. The chief umpire was favorably impressed with the Rangers' enthusiasm and spirit but noted numerous violations of doctrinal principles and sound combat techniques.

For example, the 1st Ranger Battalion became congested shortly after landing; several of its companies made excessive noise as they practiced stealth; at night, one third of the men moved while flares were being fired--an action that would have made them more visible to an enemy; the unit established itself in an indefensible position; and it failed to send local security forward after moving inland.

The 3d Ranger Battalion performed much better and was criticized only for having its landing craft too close together and moving in flare light at night.

The 4th Ranger Battalion combined several potentially fatal errors. In addition to moving while in flare light at night and failing to establish communications with Force headquarters, it moved up a road in column without sending an advance guard forward and went through a seventy-five yard long defile without first reconnoitering it." In actual combat, either of the latter two blunders could have resulted in the battalion walking into an ambush.

The number and gravity of the Rangers' errors demonstrated the decline in quality which had taken place since their formation and early training in the British Isles.

The conventional fighting to which the Rangers had too often been committed had resulted in severe attrition among their best trained and most experienced men. As their places were taken by replacements who, however brave and highly motivated, had enjoyed nothing equal to the time and training that had been lavished on the early Rangers, the Rangers' original quality became diluted and their unit cohesion weakened.

There was, however, one positive development during the period immediately preceding the landing at Anzio. The Rangers and the units that had been attached to them for the landing were designated the 6615th Ranger Force (Provisional). While there was no assurance that the unit would ever be more than temporary, for at least the time being a headquarters element was authorized that gave Darby a degree of control over the Rangers he had not previously enjoyed. On 11 December, Darby was promoted to colonel.

(4)

(4)Anzio:

The 6615th Ranger Force (Provisional) was to land at Anzio before dawn on 22 January with the mission of seizing the city's port facilities and protecting them against sabotage; destroying nearby gun batteries; clearing the beach area between Anzio and Nettuno, a neighboring town; establishing and securing a beachhead; and tying in with the British Ist Division on the left and the 3d Infantry Division on the right.

Upon contacting the 3d Division, Ranger Force would become attached to it.' All Allied forces landing at Anzio were part of Major General John P. Lucas' VI Corps.

The landing was the smoothest in which the Rangers had taken part. They landed when and where they were supposed to and met only two Germans, both of whom they killed. The other sectors of the beachhead were established with equal ease, for there were only two undermanned German coast-watching battalions to oppose the twenty-seven-battalion Al lied force. The Germans, who had come from the Winter Line for rest and rehabilitation, were quickly overrun, and by midnight VI Corps had landed about 36,000 men and 3,200 vehicles and had taken 227 prisoners at a cost of 13 killed, 97 wounded, and 44 missing. The landing was an unqualified success.

01/24/43

Twelfth Air Force Operations Log:

Weather cancels all MB and LB operations. Fighters maintain cover over Anzio beachhead (Anzio and Nettuno are captured during the day) and encounter increased air attacks. 3 fighters are claimed destroyed in aerial combat, while 1 Allied fighter is lost. P- 40 Fighter-Bombers hit road at Penne, while A-36's bomb Velletri and road junction E of town, and hit other communications targets.

Editor's Note: Protection of the Anzio Beachhead provided courtesy of the USS MAYO

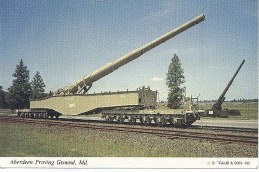

Stopping 'Anzio Annie' the Terrible German Rail-Gun

During the next few days, VI Corps cautiously expanded its beachhead, which grew to be seven miles deep and sixteen miles long by 24 January. Lucas, however, hesitated to make a decisive thrust inland and thus gave the Germans time to gather strength. When Generaloberst Eberhard von Mackensen assumed command of the beachhead defenses on 25 January, he had elements of eight divisions deployed and elements of five more on the way. Furthermore, Mackensen's mission was not defensive; he was to counterattack as soon as possible. Meanwhile, the Rangers aided in VI Corps' slow advance. By the morning of 25 January, they were nine miles inland; they would drive forward an additional two and a half miles by the morning of the 27th.

01/26/43

Twelfth Air Force Operations Log:

A-20's attack Cisterna di Latina, toward which US Fifth Army's VI Corps is moving. A-36's and P-40's fly harassing attacks against roads and railroads, bombing at Belmonte in Sabina, Cisterna, Littoria, Ceccano, Frosinone, Poggio Mirteto, and at points around these towns. A-36's destroy fuel dump and several trucks and arty caissons in Ceprano-Priverno area.

01/27/43

Twelfth AF

B-25's attack roads at Velletri, railway at Colleferro, and Military Yards at Orte. B-26's bomb bridges at Ceprano and Military Yards at Terni. A-20's give close support to US Fifth Army attack near Terelle. A-26's bomb railways and buildings at Poggio Mirteto, Ceccano, and Ciampino, hit rail and road traffic S of Rome, and, with P-40's, hit town of Piedimonte. More than 70 P-40's provide close support to Fifth Army forces in Cisterna di Latina and Atina, bombing gun positions. Allied fighters over Anzio beachhead successfully meet increased enemy air effort, claiming 28 airplanes downed in aerial combat.

01/28/43

Twelfth AF

B-25's attack Orte Military Yards. B-26's hit bridges at Orvieto and Montalto di Castro. A-20's bomb Cisterna di Latina with good results. P-40's and P-47's bomb Popoli road junction, and A-36's hit railroad, road, and gun positions in Cassino Vicenza-Velletri areas, Colleferro Military Yards, and Atina town area. P-40's hit Terelle, Belmonte in Sabina, and Cisterna. Allied fighters over Anzio area claim 21 airplanes shot down.

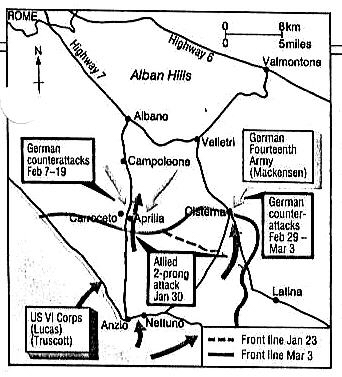

On 28 January, Clark urged Lucas to act more aggressively, and on the following day, VI Corps responded by publishing a field order outlining a major attack. There was a serious need for maintaining the Allied advance at this time. The purpose of the Anzio landing had been to threaten the rear of the Germans holding the Winter Line, forcing them to withdraw northward. This could be accomplished most effectively by seizing Highways 6 and 7, which led to Rome from the southeast and passed on either side of the 900-meter-high Alban Hills inland from Anzio. By the end of January, however, VI Corps had failed to reach the highways. If the Allies failed to break the German line, which was then on flat to rolling terrain, the Germans might withdraw to the Alban Hills. They would not only be more difficult to dislodge there but would still be able to control Highways 6 and 7 from the heights. The VI Corps attack was intended to shatter the Germans before they pulled back to the more defensible and strategic high ground.

01/29/43

Twelfth AF

B-25's bomb San Benedetto de Marsi Military Yards. B-26's hit bridges N of Rome. P-47's bomb munitions factory at Bussi sul Tirino. P-40's and A-36's, in support of US Fifth Army Forces, bomb positions in Anzio beachhead area and hit enemy forward road and rail communities. Fighters on patrol over Anzio meet little air opposition."

Cisterna:

The 3d Infantry Division, which was still commanded by General Truscott, issued its own field order in anticipation of VI Corps' order on 28 January. According to the division order, Ranger Force would cross the line of departure at 0100 on 30 January, move rapidly to Cisterna, and seize and hold the town until relieved. The 7th Infantry would operate on the left of Ranger Force, and the 15th Infantry would operate on the right. After seizing Cisterna, the 3d Infantry Division would prepare to continue the advance to take high ground near Cori and Velletri.

The mission was acceptable to Darby, who did not believe "...an attack that size could fail..."

The Rangers were relieved from their positions on line by the British during the morning of 29 January, and the battalion commanders met with Darby at 1800 that evening to discuss Ranger Force's field order.

The Force order, which was signed by Dammer and issued at Darby's command, was simple and reasonable.

The 1st Ranger Battalion would cross the line of departure, which was a road running generally parallel to and about three and a half miles south of Highway 7, and move to Cisterna under coverage of darkness by way of previously reconnoitered routes. The terrain between the line of departure and Cisterna was flat farmland with little cover other than drainage ditches and scattered farm buildings. Because the Rangers would be vulnerable in the open country, they were to use the drainage ditches for concealment when possible and avoid enemy contact before reaching their objective.

Upon arriving at Cisterna, the battalion was to enter the town, destroy the enemy in it, occupy the ground to the immediate northwest, and prepare to repel enemy counterattacks. At daylight, the battalion was to send a patrol to the northwest to contact the 7th Infantry.

The 3d Ranger Battalion would cross the line of departure fifteen minutes after the 1st Ranger Battalion cleared it and follow the 1st Rangers to Cisterna. If the enemy interfered with the 1st Ranger Battalion, the 3d Rangers were to engage them, thus freeing the 1st Rangers to continue their attack on Cisterna. The 3d Ranger Battalion would assist in the capture of Cisterna if necessary, occupy the ground immediately northeast of town, and prepare to repel enemy counterattacks. At daylight, it was to send a patrol to the northeast to contact the 15th Infantry.

The 4th Ranger Battalion, with an eight-man minesweeping party attached, would cross the line of departure at 0200 and advance on Cisterna astride the Conca-Isola Bella-Cisterna road, clearing the road of mines and enemy. At Cisterna, it would become part of Ranger Force's reserve. The Cannon Company and a platoon of the 601st Tank Destroyer Battalion would be prepared to move on Cisterna by way of the Conca-Isola Bella- Cisterna road and furnish antitank protection for Ranger Force once in Cisterna. The 83d Chemical Battalion would assemble on the Conca-Isola Bella-Cisterna road and would be prepared to move forward to positions from which it could give fire support to the advanced units.

The 3d Infantry Division G2 was optimistic and suggested that Darby's Ranger Force would accomplish its mission without undue difficulty.

While there was still a healthy respect for the ability of the higher German commanders and the quality of training and discipline found at battalion and company levels, it was noted that the enemy had not recently shown the same tenacity or 'elan that he had in the past. This was evident from the frequent surrender of small enemy groups and the enemy's lack of aggressive patrolling and was attributed in part to the integration of Poles and other politically unreliable non-Germans into German units.

As early as October 1943, a VI Corps G2 report had claimed that the number of Wehrmacht deserters appeared to be in proportion to the increasing percentage of non-German replacements. The VI Corps records also indicate that, by the end of November 1943, a German-Polish buddy system had been put into effect in some Wehrmacht units, with Germans and Poles occupying alternate fox- holes in defensive positions;

The intelligence annex to the division field order concluded, "It does not now seem probable that the enemy will soon deliver a major counterattack involving units of division size; on the other hand, the enemy will probably resort to delaying action coupled with small- scale counterattacks in an effort to grind us to a standstill, as on the Cassino line.

In spite of division's assurances, Darby's headquarters believed that enemy resistance at Cisterna might be "considerable.''

The Rangers' appraisal was the more perceptive of the two. Members of the Hermann Goering Panter Division had recently been taken prisoner in the Cisterna area."

In the past, the presence of that division in an area had indicated that the Germans were reinforcing or preparing to counterattack, but that lesson was now lost on higher headquarters.

At 2315 on 30 January, Ranger Force began to move its command post forward from a location well behind the lines, and by 0215 the next morning, it had reached its site, an isolated house near the line of departure and just to the right of the Conca-Isola Bella-Cisterna road."

Darby would direct the attack from the house and, as the battle progressed, from positions forward.

The 1st and 3d Ranger Battalions passed through the line of departure that night as planned and began to move toward Cisterna through a ditch that offered cover and concealment. At 0248, however, the first of several events took place that did not augur well for the mission.

Four radio operators who were to have accompanied the 3d Ranger Battalion reported themselves lost to the Force command post.

Darby, always conscious of the need for good communications, thought it "the god-damnedest thing" he had "ever heard of."

A second problem developed when the 3d Ranger Battalion lost contact with the 1st Rangers about halfway to the objective.

Then, a half mile ahead, the 1st Ranger Battalion became split in two, with three companies continuing to advance and three remaining in place.

The dangers of conducting a night infiltration with so many relatively untrained and inexperienced men were becoming painfully evident.

Captain Charles Shunstrom took command of the 1st Ranger Battalion's three rear companies and sent a runner back to find the 3d Ranger Battalion.

The runner returned with word that Major Alvah Miller, who had only recently been made the 3d Ranger Battalion commander, had been killed by a round from a German tank and that the battalion was moving forward to link up with the 1st Rangers.

Although Miller's death demonstrated that the Germans were probably aware that something was afoot, there was no systematic attempt to stop the Rangers and no reason to believe that the Germans knew the scope or objective of the operation.

On the contrary, the 1st Ranger Battalion appeared to be having continued success spearheading the operation.

Graphic used with Permission Northwestern University Library

(Editors Note: Later Intelligence Analysis of the Rangers Radio Communications indicated that the Germans were probably more aware of the Ranger Force's operations than was believed at the time of the Battle)

Although German patrols crossed in front and on both sides of the battalion, they did not appear to be aware of the Rangers' presence, and two groups of German sentries were surprised by the point and killed with knives. Lieutenant James G. Fowler, who led the point, personally killed two of the enemy.

At about 0545, with the first light of day, the 1st Rangers passed close enough to an enemy artillery battery to hear the gunners' voices. They did not fire on the Germans but tried to radio Darby.

They failed to make contact and continued to creep forward through some empty trenches until they reached a flat field on the southern edge of Cisterna.

(Looking northward toward Cisterns from the vicinity of Isola Bella. The shoulder of the ConcaIsola Bella-Cisterna road is to the immediate left, and the Alban Hills are faintly visible on the horizon. The 1st and 3d Ranger Battalions infiltrated toward their objective through the fields and fought their last battle just short of Cisterna's houses, the rooftops of which were visible beyond the trees to the front. A virtual absence of concealment)

The field was roughly triangular in shape, about a thousand yards long on each side, and surrounded and subdivided by roads and drainage ditches. The Rangers began running toward Cisterna in the hope of reaching it before the sun rose.

When about six hundred yards outside the town, they passed through what seemed to be a German bivouac area and killed a large number of the surprised enemy with bayonets and knives.

When they had run 400 yards farther and reached the edge of Cisterna, they were stopped by violent fire from the town. They returned fire from a position astride a road that paralleled an irrigation ditch. It did not provide much cover, but it was all the Rangers had.

The 3d Ranger Battalion and the three companies of the 1st Ranger Battalion that had been separated were able to get within 300 yards of the three lead companies before running into the Germans. After Ranger bazooka-men destroyed two tanks that had been blocking the way, Shunstrom went forward with a runner and two other men and made contact with Major Jack Dobson, who briefed him on the situation. Dobson, who was new to the Rangers, had been given command of the 1st Ranger Battalion by Darby shortly before Anzio.

The 4th Ranger Battalion began its attack up the Conca-Isola Bella-Cisterna road as scheduled but was stopped short of Isola Bella by fire from German tanks, self-propelled guns, automatic weapons, and small arms. Cisterna was more strongly held than anyone had anticipated.

Darby, who was gravely concerned about the virtually nonexistent communications he had with the two lead battalions and the difficult time the 4th Rangers were having, saw well the urgent need to break through the German roadblock. Indeed, the survival of the 1st and 3d Ranger Battalions depended on his doing so.

Although it was not fully realized at the time, the circumstances in which Darby found himself were the results of conscientious planning by the Germans and poor intelligence by the Americans.

General Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, the senior German commander in Italy, had correctly judged Lucas to be too cautious to move directly on the Alban Hills and had concentrated considerable strength in Cisterna in preparation for a counterattack that had been scheduled for 2 February.

This counterattack continued to be unexpected by American intelligence, which had interpreted German intentions in the area to be "purely defensive."

Kesselring, however, had correctly judged the probability of an American attack on Cisterna and took steps to blunt it. A German officer, who took part in the battle and was later captured, stated in his interrogation that Cisterna had been reinforced by elements of the Hermann Goering Panzer Division on the night of 29 January in anticipation of the attack.

+ Tamiya Model: German Tiger Tank +

Ironically, a young Pole named Stempkofski who had been serving in the Wehrmacht made a vain attempt to warn the Americans of the German preparations. He deserted to American troops and tried to tell them what was happening, but they evacuated him to the rear and his story was not known until after the battle when he was routinely interrogated at Fifth Army headquarters.23

Also unknown to Darby was another fact; the Germans had detected the 1st and 3d Ranger Battalions as they moved northward about a mile south of the triangular field.

The appearance of three German tanks to the 1st and 3d Ranger Battalions' rear while Dobson was briefing Shunstrom indicated to the Rangers that they were being surrounded.

All three tanks were destroyed by rocket gunners, but automatic and small arms fire continued to tear through the Rangers, most of whom had gathered in an area about three hundred yards in diameter.

German attempts to overrun the Rangers, and Ranger attempts to break out of the encirclement, were turned back with mutual ferocity.

After two hours, the Rangers' ammunition began to run short, and three companies that were being held in reserve within the battalions' perimeter gave half their ammunition to the companies on line.

Meanwhile, the Germans grew in strength as the newly arrived 2dParachute Lehr Battalion, which was regularly used to reinforce threatened sectors of the front, and armor, NebelLuerfer, flak wagons, and artillery firing at pointblank range brought their power to bear on the Rangers.

The besieged Americans repeatedly called for help by radio, but what messages got through in spite of the Rangers' imperfect communications were sent in vain, because Darby and the rest of Ranger Force had been fought to a standstill south of Isola Bella.

(Editors Note: The German parachute unit at Cisterna was officially a provisional unit which had begun formation in May of 1943; the 4.Fallschirm-Jager-Division. They had started their reorganization at Venedig (Venice) from the following units: I/FJR.2, II/FJR.6, and I./Luftlande-Sturm-Regiment.1 (all ex-2.Fallschirm-Jager-Division) and a large contingent of the DEMBO and FOLGORE Italian Parachute Divisions. The 4.FJR won a reputation for toughness and reliability following Anzio and Cisterna; it surrendered in May 1945 in Northern Italy)

Shortly after noon, enemy paratroopers supported by armored personnel carriers began marching about a dozen captured Rangers toward the center of the 1st and 3d Ranger Battalions' position in an attempt to force an American surrender. Ranger marksmen shot two German guards, but the Germans retaliated by bayoneting two of the prisoners and continued to march the rest forward. The same sequence was repeated a second time - two Germans were shot and two prisoners were bayoneted. This time, however, more Rangers surrendered.

The Germans continued to march their captives, now numbering about eighty, toward the center of the Rangers' position shouting that they would shoot the prisoners if the remaining Rangers did not surrender.

For a third time, the surrounded Americans opened fire, but when several prisoners were accidentally killed along with one or two Germans, a few men "who were evidently new to combat got hysterical and started to leave their positions and surrender."

They were ordered not to give up but continued to do so, and the piecemeal surrender continued: Even an attempt by the more determined Rangers "to stop" those who wished to surrender "by shooting them" failed.

Calmer men disassembled their weapons and buried or scattered key parts before the Germans overran the area. Others destroyed radios after telling Darby what was happening. Robert Ehalt, sergeant major of the Ist Ranger Battalion, was the last man to speak to Darby by radio from Cisterna.

Ehalt told Darby that the commander of the 1st Ranger Battalion had been wounded and the executive officer of the 3d Ranger Battalion killed. He himself had only five men left, and German tanks were closing in.

"So long, Colonel," Ehalt concluded, "maybe when it's all over I'll see you again."

Darby told Ehalt that he would never forget the surrounded men and would be with them till the end. Ehalt then destroyed his radio and continued to fight on for a while longer with the few men he had left before surrendering."

Other painful dramas, much like Ehalt's, were played out in the triangular field as the heavily equipped Germans, using farmers' access roads for their armor, broke the Rangers into ever smaller groups and captured them or annihilated them in detail.

By the end of the day, the 1st and 3d Ranger Battalions had ceased to exist. Only 6 of the 767 men who had infiltrated to Cisterna made their way back to friendly lines. All the others had been killed or captured.

B-25's hit road junctions at Valmonte and Genzano di Roma, and bomb town of Monte Compatri. Weather cancels all B-26 operations and several B-25 missions. A-20's hit town of and road junction near Cori, and XII A Spt Cmd Fbs hit Sora. US and British fighters hit Barges and fishing boats of Zara and Trojica. Fighters on patrol over Anzio meet no air opposition.

Commentary:

While Darby was recovering from losing most of his command, his superiors were already beginning to avoid or obscure responsibility for the debacle. Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark, commanding general of Fifth Army with overall responsibility for the landing at Anzio, had it entered in his diary that he was "distressed to find that the 3d (Infantry) Division had led with the Ranger force in its attack on Cisterna. This was a definite error in judgment for the Rangers do not have the support weapons to overcome the resistance indicated."

Out of fairness to Clark, he had not been involved in the detailed planning of the attack on Cisterna and did not know that the Rangers had been chosen to lead the way." Indeed, he would have been violating the chain of command had he bypassed VI Corps' headquarters to tell a division commander how to plan an attack.

A report prepared by VI Corps' G1 professed that, had the attack on Cisterna succeeded, "it would have been a brilliant tactical move with far- reaching effects upon the operations in this area. Its failure was an incident of campaign contributed to by so many factors that it can be ascribed only to chance."

The G1 would have placed the blame more squarely if he had laid it on poor intelligence. Although sufficient information had been collected to correctly determine the enemy's capabilities and probable course of action, they had been sorely misjudged.

Although poor intelligence was most important in determining the outcome of the battle, the Rangers contributed to their own end, though to an indefinite degree. While the Germans expected an attack on Cisterna, they had no definite knowledge of precisely when or where it would take place. This was learned during the infiltration phase, when the Germans discovered the Rangers' presence. In view of the difficulty the Rangers had practicing stealth while training at Pozzuoli Bay, their ability to successfully conduct an operation such as they attempted at Cisterna is open to question. That the Rangers surprised and overran bivouacking enemy just outside the objective was probably due to a breakdown in the Germans' communications and their consequent failure to inform all their troops that the Rangers were in the area.

However much or little it may have contributed to the outcome at Cisterna, the decline in the Rangers' combat skills was an unfortunate result of misusing the Rangers. From North Africa through Italy, the Rangers had been too frequently used as conventional infantry, and most of their casualties were suffered in those actions. As Ranger casualties were replaced with less well-trained men, Ranger Force's quality became diluted, the level of its combat skills declined, and unit cohesion weakened. This deterioration was evident throughout the battle.

Although Darby's Ranger Force failed to accomplish its mission at Cisterna, it contributed at suicidal cost to the eventual victory. The battle for Cisterna was sufficiently jarring to the Germans to force them to delay their plans two days. They did not launch their counterattack until 4 February (thus giving the Allies forty-eight extra hours to prepare) and then failed only by the narrowest of margins, reducing some American units to firing artillery over open sights and using clerks and cooks as riflemen. Had the attack on Cisterna not taken place and had the Germans been able to counter attack earlier, the outcome might have been different.

Subsequent Developments:

Cisterna marked the beginning of the end of Darby's Ranger Force.

The 4th Ranger Battalion helped turn back the German counterattack of 4 February, and on 19 February, those Rangers still surviving were temporarily attached to the Canadian-American 1st Special Service Force. Their experience was put to further good use in the spring when they were assigned to conduct a scouting and patrolling school for Fifth Army outside Civitavecchia, near Naples. Rangers of long standing were sent to Camp Butner, North Carolina, on 6 May and remained there until 24 October when the Ist, 3d, and 4th Ranger Battalions were inactivated. Those men who had joined the Rangers more recently and had not spent enough time overseas to justify being re- turned to the United States were absorbed into the 1st Special Service Force.

Editors Note:

February 17th 1944

TACTICAL OPERATIONS (Twelfth Air Force): In Italy, B-26s bomb the bridge approach S of Manziana; B-25s hit the Viterbo marshalling yard and, in support of US Fifth army troops, bomb the town of Cisterna di Latina as the enemy counterattack begins in the Anzio area; A-20s hit Piedimonte and the road junction and railway station at Campoleone; A-36s hit San Stefano al Mare and nearby railroad siding, Pontecorvo and Belmonte in Sabina, plus several targets of opportunity and targets in support of ground forces in the battle areas; P-40s attack an observation tower at Littoria, trucks at Villa Santa Lucia degli Abruzzi, Campoleone, a railroad gun, the Sezze railroad yards, Cisterna di Latina and gun positions in battle areas. Fighters encounter heavy aircraft activity over the Anzio battle area and claim 16 shot down. (5)

Darby briefly commanded the 179th Infantry during the German counterattack at Anzio and was assigned to the Operations Division of the War Department General Staff in Washington, DC, in April 1944.

17 April 1944

M-4 Medium Tank put ashore by LST 77, Anzio Harbor Fifth Army

(Photo Used with Permission US Amy Military History Files)

While in Washington, Darby had a conversation with William Hutchinson that demonstrated, once again, his faith in firepower. He told Hutchinson that his experience with the 179th Infantry had impressed him with the might that could be brought against an enemy by a unit that was several times larger than his Ranger Force and had direct access to the firepower of division artillery. With such an infantry unit trained in Ranger operations, Darby believed that he could do what he had done with the Rangers, but on a larger scale.

Events, however, did not afford Darby the opportunity to test his theory. After spending a year in Washington, he became assistant division commander of the 1Oth Mountain Division then fighting in northern Italy. He was killed by a round from a German 88-mm gun in Torbole, Italy, on 30 April 1945, while visiting the front.

(2)

(2)SYNOPSIS OF LEAVENWORTH PAPER 11

This Leavenworth Paper examines five operations that US Army Rangers conducted during World War II. Although these are but a small number of the Rangers’ operations, they are highly representative, for they were conducted against the armies of three enemy nations in five geographical areas and had varying results.

In March 1943, the 1st Ranger Battalion, in cooperation with conventional infantry, infiltrated Italian lines in Tunisia and attacked a defensive position at Djebel el Ank. The Rangers took their objective and 200 prisoners without losing any of their own men. In July 1943, the 3rd Ranger Battalion advanced through disintegrating Italian lines to capture the Sicilian port city of Porto Empedocle. The Rangers took the city and capture 675 Italians and 91 Germans at the cost of 1 of their own dead. The number of enemy dead at Djebel el Ank and Porto Empedocle was not recorded.

In January 1944, the 3d and 4t Ranger Battalions participated in the Cisterna operation as part of a greater Allied attempt to expand the Anzio beachhead. It was one of the most severe small-unit disasters of the war, and the Rangers lost all but 6 of their 767-man force.

In January 1945, elements of the 6th Ranger Battalion conducted a raid behind Japanese lines near Cabanatuan City in the Philippine Islands to liberate the inmates of a POW compound. They killed or wounded an estimated 523 Japanese and freed 511 American and Allied prisoners at the cost of 2 of their own dead.

In February 1945, the 5th Ranger Battalion infiltrated enemy lines near Zarf, Germany, and occupied high ground to its rear. During the movement and the three-day battle that followed, the Rangers killed an estimated 299 enemy troops and took 328 prisoners while themselves suffering more than 90 casualties.

Many circumstances contributed to the results of these five operations. In Leavenworth Paper No. 11, they are examined in detail and lessons are drawn. The historical backgrounds of the Ranger battalions are also provided to place the five operations in perspective.

Unclassified

(Edited format and in some cases spelling corrections; the other five operations not provided to this editor)

(1) Source Public Domain: 1985: Also furnished by Frank A. Burdick; GS-18 FBIS, Retired 1985

(2)"Keep it Up Brother..." Used with Permission Northwestern University Library

(3) "Hope it's Not a Dud..." " " Northwestern University Library

(4) Anzio Map Courtesy of Tom Pace Collection: US Army Special Forces 1979

(5) http://paul.rutgers.edu/~mcgrew/wwii/usaf/ by Jack McKillop which details air operations for every day of WWII

(6) Twelfth Air Force Logs:http://www.airforcehistory.hq.af.mil/chron/44jan.htm

A special posthumous thanks to Intelligence Officer Frank Burdick.

Navy Veteran & Army Veteran of WW II, Intelligence Operations Korea & Vietnam. Frank sneaked into the Navy at 16! He saw action in the Pacific; later he was discharged for his age;

at 17 he reenlisted in the Army before the War was over and saw infantry combat; he received a battlefield commission to 2nd Lt. and was later wounded and 100% medically discharged.

He continued to serve his country until retirement with the DOD, Joint Military Intelligence Operations and FBIS. For me to be one of 'Burdick's Boys' was a privilege and the Highest of Military Honors. Frank's love for his country and his dedication to our mission was unequaled; and his leadership and knowledge of Intelligence operations has remained an inspiration for me

in all my endeavors spanning more than twenty years.

(Editor-Bob Price)